The Evolving Legacy of Crispus Attucks, 1770-1863

Inquiry Question 1: In what ways have people of color been both present for and critical actors in turning points in American history?

Inquiry Question 2: How and why has public memory of the Boston Massacre changed over time? In what ways do available evidence and point of view impact interpretations of historical events?

- Background Reading for Students

-

British Soldiers on Trial: In the fall following the Boston Massacre (March 5, 1770), the eight British soldiers who fired into a crowd of colonists, killing five, were put on trial for murder. Crispus Attucks, a Black and Indigenous sailor, was the first man killed at the massacre, and his role in the events that night became contested during the trial. Townspeople who had witnessed the event gave testimonies in court, describing what they saw that night and lawyers for both sides asked witnesses what they saw Attucks do and say. John Adams was a member of the Sons of Liberty, but he was also the defense lawyer for the soldiers. Although only the soldiers had guns, Adams blamed Crispus Attucks and the other victims for making the soldiers feel unsafe. Adams said the soldiers were forced to defend themselves. Ultimately, the jury agreed. Captain Preston and six of the soldiers were found “not guilty.” Two other soldiers were found partly “guilty” and spent time in jail. However, the British government removed the soldiers from Boston.

Remembering the Massacre: In the years after the trial Patriots continued to remember and honor the victims each year on March 5th. John Hancock told colonists that the British taxes had been unfair and that the presence of an army in a town during times of peace was dangerous and could become violent. Many years after the Revolutionary War ended, in the mid-1800s, people began to look at the Boston Massacre as the beginning of the Revolutionary War. Black abolitionists began to start talking more about Crispus Attucks, but this time they celebrated him as the first martyr of the Revolution. They argued that Black people should have equal rights and that their participation in the Boston Massacre and the Revolutionary War showed that Black Americans had always been committed to freedom and independence.

Source Set

For elementary, use this Google slide deck to explore the sources.

Glossary

Abolition / Abolitionist:

the movement to bring an immediate end slavery in the United States. An abolitionist was someone involved in this movement

Commemorate / Commemoration:

to show respect for someone or something. A commemoration is an official act of remembering people or events from the past

Martyr / Martyrdom:

someone who is killed for their beliefs. Martyrdom refers specifically to the death of the martyr

Oration:

a formal speech given in front of an audience

Testimony / testify:

a formal recorded statement typically taken to be used in court. To testify is the process of providing the statement under oath

Analyzing Point of View & Purpose

Who is telling this account of the events surrounding the Boston Massacre and Crispus Attucks?

What is the relationship between the source creator and the events of the Massacre?

At the time when this source was created, what types of people held power in the United States (politically, socially, economically)? Were these positions of power being challenged? How does that connect to this source’s purpose or point of view?

What is the tone and language of the source creator when referring to Crispus Attucks and the Boston Massacre? How can this help us understand the point of view of the creator and the purpose of the source?

For Sources 4-9:

How does the author use the Boston Massacre and Crispus Attucks to meet their purpose or agenda in later eras of American history?

Created by MHS staff, Abigail Portu, Kate Bowen, and Ben Remillard, PhD

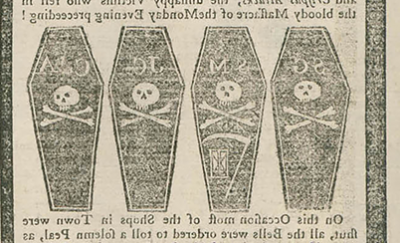

The mulatto man, named Crispus Attucks, who was born in Framingham, but lately belonged to New Providence and was here in order to go for North Carolina, also killed instantly; two balls entering his breast, one of them in special goring the right lobe of the lungs, and a great part of the liver most horribly.

Printed exactly one week after the tragedy, this newspaper report from The Boston Gazette and Country Journal provided comprehensive coverage of the Boston Massacre. Descriptions included conflicts between Bostonians and soldiers leading up to 5 March 1770 and details from the night of the event summarized from witness accounts. Crispus Attucks is directly mentioned three times in the piece. The Gazette is considered to be one of the most influential publications of the Revolutionary era in America.

Citation: "Boston, March 12. The Town of Boston affords a recent and melancholy Demonstration ..." Article from pages 2-3 of The Boston-Gazette, and Country Journal, Number 779, 12 March 1770, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://3721.use-iphone.com/database/316.

Q. Did you see a number of persons coming up Royal-exchange-lane, with sticks?

A. No, I saw a number going up Cornhill, and the Molatto fellow [Attucks] headed them.

…

Q. What did the party with the Molatto [Crispus Attucks] do or say?

A. They were huzzaing, whistling and carrying their sticks upright over their heads.

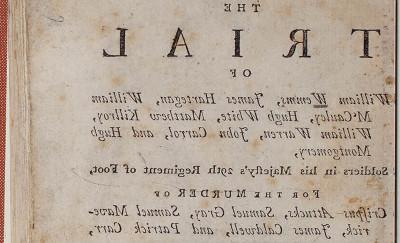

James Bailey, a sailor, witnessed the Boston Massacre and the conflict at the ropewalks a few days earlier. Bailey was called by the defense to testify as part of the Rex v. Wemms et al. trial. On the night of 5 March 1770, Bailey was not part of the so-called mob, but spent time talking with the British soldiers, who he knew well. In his testimony, Bailey described what he claimed to see Crispus Attucks and others do and say, and the defense used his account as evidence that the soldiers fired in self-defense.

The trial transcript was taken in short-hand by John Hodgson, and this 210-page pamphlet covered the trial and verdict.

Citation: "The Annotated Newspapers of Harbottle Dorr: The Trial of William Wemms, James Hartegan, William McCauley, …" pamphlet recounting the trial and verdict of several perpetrators of the Boston Massacre, c. 1770s, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://3721.use-iphone.com/847

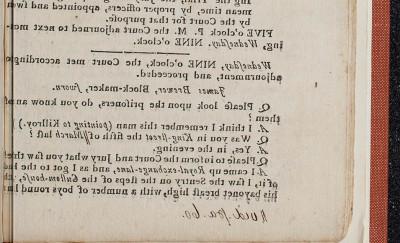

Q. Were there any [Bostonians] coming up Royal Exchange lane?

A. Yes, numbers, but I saw no sticks.

Q. When you first saw [Attucks], did you hear him say any thing to the soldiers, or strike at them?

A. No.

Q. Did you hear any huzzas or cheers as they are called?

A. I heard a clamour of the people, but I heard no cheers

Bostonian James Brewer, a pumpmaker and blockmaker, was called to testify in the Rex v. Wemms et al. trial by the prosecution. While Brewer said that he was not close enough to the British soldiers the night of the Boston Massacre to identify all of their faces, he gave a clear account of his view of the night’s events. Brewer's testimony contradicted Bailey's account and the prosecution used it to attempt to portray the British soldiers as the aggressors that night.

The transcript of the trial was taken in short-hand by John Hodgson and printed in the same 210-page pamphlet as “Trial Testimony on Attucks by Bailey” (Source 2), among others.

Citation: "The Annotated Newspapers of Harbottle Dorr: The Trial of William Wemms, James Hartegan, William McCauley, …" pamphlet recounting the trial and verdict of several perpetrators of the Boston Massacre, c. 1770s, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://3721.use-iphone.com/847

To have this reinforcement coming down under the command of a stout Molatto fellow, whose very looks, was enough to terrify any person, what had not the soldiers then to fear? . . . This is the behavior of Attucks; – to whose mad behavior, in all probability, the dreadful carnage of that night, is chiefly to be ascribed.

As a defense lawyer for the accused soldiers, John Adams chose to highlight the witness testimony that best helped him frame Attucks as one of the key perpetrators of the Massacre. Strategically, Adams drew attention to Attucks’s status as a stranger, or as an outsider not belonging in Boston. Attucks had fled from slavery in nearby Framingham, and had not obtained a residence in Boston, making it easy for Adams to portray him as an outsider. Adams then drew specific attention to Attucks’s race as a way of further vilifying him in the eyes of Boston’s majority-white population.

Citations: John Adams, Portrait by Benjamin Blyth, circa 1766, Massachusetts Historical Society, 3721.use-iphone.com/database/40

"The Annotated Newspapers of Harbottle Dorr: The Trial of William Wemms, James Hartegan, William McCauley, …" pamphlet recounting the trial and verdict of several perpetrators of the Boston Massacre, c. 1770s, Massachusetts Historical Society, p. 176, http://3721.use-iphone.com/dorr/volume/3/sequence/1003

Do not the injured shades of Maverick, Gray, Caldwell, Attucks and Carr, attend you in your solitary walks, arrest you even in the midst of your debaucheries, and fill even your dreams with terror?

On 5 March 1774, John Hancock delivered an oration to a crowd in Boston in commemoration of the Boston Massacre. The speech itself would have lasted around 25 minutes. To reach a wider audience, it was then printed in this pamphlet, which was published by Edes & Gill, the printers of the Boston Gazette (Source 1). By 1774, Hancock was already a well known patriot and member of the Sons of Liberty. In his oration, Hancock focused on the dangers of a standing army and argued that colonists may need to risk their lives again to continue to fight for their rights.

Citation: "The Annotated Newspapers of Harbottle Dorr: An Oration Delivered March Fifth, 1774," annotated pamphlet, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://3721.use-iphone.com/1290

The rejection of the petition [for a monument to honor Attucks as the first martyr of the American Revolution] was to be expected, if we accept the axiom that a colored man never gets justice done him in the United States, except by mistake.

- William Cooper Nell, Colored Patriots of the American Revolution, 1855 (p. 18)

William C. Nell was a Black leader and community organizer in Boston’s abolitionist movement from the 1840s through his death in 1874. He wrote for William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator and Frederick Douglass’s The North Star while also actively working to integrate Boston’s public schools. In 1855, Nell wrote The colored patriots of the American Revolution: with sketches of several distinguished colored persons: to which is added a brief survey of the condition and prospects of colored Americans, which included an introduction written by Harriet Beecher Stowe, best known as the abolitionist author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Nell was one of the first notable Black historians of American history, and his book, which begins with Crispus Attucks, details the contributions of Black Revolutionary War soldiers.

Citation: William C. Nell (1816-1874), photograph, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://3721.use-iphone.com/database/1338

Attucks had formed the patriots in Dock Square, from whence they marched up King street… to make the attack…He had been foremost in resisting, and was first slain.

- William Cooper Nell, Colored Patriots of the American Revolution, 1855 (p. 16)

In 1856, William L. Champney chose to honor the events of 5 March 1770 with a new version of Paul Revere’s “Bloody Massacre perpetrated in King Street.” The image was reprinted and distributed the following year by one of Boston’s best lithography studios. The previous years in antebellum America had seen the Compromise of 1850 and implementation of the Fugitive Slave Act, as well as the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which led to increased division between Northern and Southern states and a rise in the abolitionist movement.

Citation: "Boston Massacre, March 5th 1770," Lithograph by J.H. Bufford’s Lith., after W. Champney, Boston: Published by Henry Q. Smith: J.H. Bufford’s Lith., 1856, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://3721.use-iphone.com/database/3040

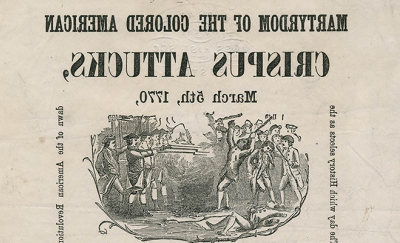

In 1863, William C. Nell (see source 6) helped to organize an event to commemorate the 93rd anniversary of the Boston Massacre, which focused on the “martyrdom” of Crispus Attucks. These events, which were popular during the American Revolution (see source 5), found a resurgence of support in the years leading up to and during the American Civil War. Among the featured attendees in 1863 were Colonel Robert Gould Shaw and the Massachusetts 54th Regiment, one of the first Black regiments to serve in the U.S. Civil War.

These later commemorations staked the claim that Black Americans deserved rights of full citizenship in the present because they, too, had fought for American independence.

Citation: "Martyrdom of the Colored American Crispus Attucks!: March 5th, 1770..." broadside, 1863, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://3721.use-iphone.com/database/6516

For Teachers

Download source set (grades 8-12)

Story of Boston Massacre and Legacy of Crispus Attucks Google Slides (grades 3-5)

The Evolving Legacy of Crispus Attucks, 1770-1863

Background Reading

- The Evolving Legacy of Crispus Attucks, 1770-1863: Historical Context

-

Written by Ben Remillard, PhD

Crispus Attucks is most often remembered for being the American Revolution’s “first martyr” after he was killed during the Boston Massacre. Since his death, Attucks has become a symbol for Black Americans’ ongoing sacrifices and contributions to American history. But beyond his death the night of the Massacre, we know little about him for certain.

While Attucks is often referred to in colonial reports as a mixed-race “molatto” man (an outdated and racist term describing someone descended from white and Black parents), he was most likely a mixed-race man of African and Indigenous descent. This rationale is based on a few scattered facts. It is likely he was a formerly enslaved man whose enslaver placed an ad for “a Molatto fellow, about 27 Years of Age, named Crispas,” who “ran away from his Master, William Brown, of Framingham.” Historians have generally come to the conclusion that Attucks’s mother was a Native American woman from nearby Natick, which was founded by colonists as a “praying town” for converted Christian Indians. Filling in some of the sparse details of Attucks’s life, we have one source that describes him as a sailor. Perhaps he made his living contributing to Britain’s mercantile empire. His life as a sailor, however, might have brought him into conflict with British soldiers, whose numbers in Boston increased dramatically after the Seven Years’ War. The redcoats’ presence at times caused tensions with the local populace, especially with Boston’s laborers, whom the soldiers sometimes undercut in their search for off-hours work. John Adams noted that the relationship between sailors and soldiers was defined by hostility, “that they fight as naturally when they meet, as the elephant and the Rhinoceros.” One such fight broke out just a few days before the Massacre, where a group of soldiers brawled with workers at a ropewalk (where men wound fibers together to make the ropes needed to sail ships). These ongoing tensions might explain why Attucks and other “jack tars,” a.k.a., sailors, rushed to the conflict the night of the Massacre, though even this is circumstantial speculation.

What we know of Attucks’s involvement in the Boston Massacre comes from witness testimony given during the ensuing trial, where the British soldiers were accused by Boston’s colonists of murder. But this is where things get tricky for historians, as the available primary sources give us multiple vantage points from which we can view the Massacre. While some Bostonians claimed Attucks was removed from the front lines and that he did not do anything to antagonize the soldiers, other witnesses placed the mixed-race man at the head of the conflict.

As a defense lawyer for the accused soldiers, John Adams took advantage of these differing accounts, picking out the testimony that best helped him frame Attucks as one of the key perpetrators of the Massacre. One tactic the lawyer used was to draw attention to Attucks’s status as a stranger, or as an outsider not belonging in Boston. Given that Attucks fled from slavery in nearby Framingham, and because he had not obtained a residence in Boston, it was easy for Adams to alienate Attucks and portray him as a foreign interloper. Adams then drew specific attention to Attucks’s race as a way of further vilifying the slain man in the eyes of Boston’s predominantly white populace.

It is important to remember, however, that Attucks was not the only person of color at the Massacre, and that people of color in Boston experienced the Massacre and the Revolution in different ways. As a vital part of Britain’s trans-Atlantic empire, Boston reflected the multi-ethnic nature of Massachusetts’s busy capital. This included a combination of over 1,500 enslaved and free Black people who comprised about ten percent of the port’s population in the middle of the eighteenth century.[6] Two of these Black men were called by Adams to serve as defense witnesses during the trial. One of them was an emancipated man named Newton Prince. As a free and active member of Boston’s growing community, Prince made his living as a lemon merchant and pastry chef, and was a member of Boston’s Old South Meeting House—a Congregational church that served as an important site for the Patriots in the years prior to the War for Independence. When called to give his testimony at the trial, Prince agreed with other witnesses who described the crowd as aggressive, with some civilians getting close enough “with sticks striking on their [the soldiers] guns.” The colonists, Prince said, taunted the soldiers, saying “fire, fire damn you fire, fire you lobsters, fire, you dare not fire.”

Andrew, an enslaved man, was similarly summoned to give testimony regarding the crowd’s taunts, their encroachment on the soldiers, and the crowd’s throwing of “snow balls, and other things, which then flew pretty thick.” Andrew asserted that Attucks struck at the soldiers, saying that Attucks, “a stout man with a long cord wood stick, threw himself in, and made a blow at the officer.” According to Andrew’s testimony, Attucks “then turned round, and struck the Grenadier's gun at the Captains right hand, and immediately fell in with his club, and knocked his gun away, and struck him over the head,” and cried out, “kill the dogs,” enticing the crowd in closer.[8] Despite the claim by another witness, James Bailey, that “It was not the Mollato [Attucks] that struck Montgomery,” it was Andrew’s account that Adams used to portray Attucks as the malicious instigator of the Massacre.

Detailing Attucks’s supposed role at the head of a group who approached the soldiers, Adams described his defendants as having little choice but to act in self-defense against such an imposing force: “to have this reinforcement coming down under the command of a stout Molatto fellow, whose very looks, was enough to terrify any person, what had not the soldiers then to fear?” Drawing attention to Attucks’s race and alleged “mad behaviour,” Adams pinned the blame for the Massacre squarely on the self-emancipated man, whom the future president argued, “in all probability, the dreadful carnage of that night, is chiefly to be ascribed.” Adams’s defense worked, and he prevented the soldiers from being sentenced for murder. Although two of the defendants were convicted of manslaughter given the evidence that they fired into the crowd, even those sentences were eventually reduced from hanging to a simple branding on the thumb.

Despite the attention Adams drew to Attucks’s race during the trial, the Patriots quickly obscured the participation of men of color at the Boston Massacre. While the earliest reports told of Attucks as a “mulatto” man, the Whig press soon after stopped mentioning Attucks’s race. Instead, they grouped him in with the rest of the victims by referring to each as “mister.” This, the historian Mitch Kachun argues, would have suggested to contemporary readers that all the dead men “were both respectable and white.” The most well-known example of this racial whitewashing can be seen in Paul Revere’s famous engraving of the Massacre, which shows a sea of defenseless white gentlemen being victimized by an organized line of British soldiers. While some later reprints included Attucks with darker physical features than the rest of the crowd, the majority of the surviving images we have depict him as a white man. By portraying the Massacre in this way, Revere and others erased Attucks and other people of color from the evening. Doing so reframed one of the earliest events of the Revolution as an entirely white affair. Similarly, at Boston’s annual commemorations in the years after the Massacre, Attucks’s heritage was never mentioned, creating a tradition whereby his race was obscured from popular memory. This plays into a larger trend during and after the Revolution, when the contributions of Attucks and other people of color were quickly forgotten by many white Americans despite the roles played by roughly 6,000 Patriots of color who took part in the War for Independence. Attucks, however, would not remain in the shadows.In 1855, eighty-five years after the Massacre, Attucks’s role in the event was brought to new, widespread attention in William Cooper Nell’s The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution. Nell and other Black, Civil War-era abolitionists and activists wanted to show audiences that Black Americans had always been a part of American history, and that they had always been ready to lay down their lives for liberty. One of Nell’s primary sources for his account of the Massacre came from the Italian historian Charles Botta’s History of the War of the Independence of the United States of America. Botta’s work, in turn, took much from Adams’s defense arguments regarding the rowdy crowd “under the command of Attucks,” who the lawyer argued, had “undertaken to be the hero of the night.” Botta—and by extension, Nell and later writers—prioritized the testimony describing how Attucks took an active role in the lead-up to the Massacre. Nell even borrowed directly from Botta’s description of the evening:

a band of the populace, led by a mulatto named ATTUCKS, who brandished their clubs, and pelted them [the soldiers] with snowballs […] at length, the mulatto and twelve of his companions, pressing forward, environed the soldiers, and striking their muskets with their clubs, cried to the multitude: 'Be not afraid; they dare not fire: why do you hesitate, why do you not kill them, why not crush them at once?' The mulatto lifted his arm against Capt. Preston, and having turned one of the muskets, he seized the bayonet with his left hand, as if he intended to execute his threat. At this moment, confused cries were heard: 'The wretches dare not fire!' Firing succeeds. ATTUCKS is slain.

While Adams’s account of the Massacre vilified Attucks, whose ‘mad behavior’ was to blame for the deaths of the five men during the Massacre, Botta and Nell interpreted the slain man’s actions differently. Although Nell also argued that Attucks led the protest against the British soldiers, he describes Attucks as a hero who was “of and with the people” in their act of rebellion against oppressive British rule. In so doing, Nell highlighted Attucks as the first in a long, documented line of patriotic Black Americans. With Attucks’s martyrdom at the forefront of these new histories, Black writers hoped to show the nation that Black Americans were deserving not only of freedom from slavery, but also of equal rights. Another one of these Black, Civil War-era activists, William Wells Brown, asserted that “Whenever the rights of the nation have been assailed, the negro has always responded to his country’s call, at once, and with every pulsation of his heart beating for freedom.”

These lessons were built upon in public events that highlighted the lives and deaths of men like Attucks. This included, for example, during the Civil War, when a Boston Massacre commemoration was held on March 5, 1863, highlighting the “Martyrdom of the Colored American Crispus Attucks.” The event promised to feature the white Colonel, Robert Gould Shaw, and members of the Massachusetts 54th Regiment, which had become famous for being the first Union regiment to include Black recruits.

So while the earliest commemorations of the Massacre in the 1770s overlooked Attucks and his race, nineteenth century audiences and commentators were more than willing to highlight his life and death. In doing so, they connected his sacrifice with their own contemporary struggles to better the lives of Black Americans.

These calls for equality were repeated following America’s participation in the World Wars, when Black Americans argued that equal rights were deserved given their ongoing service and sacrifices in the nation’s wars. Attucks was frequently cited in these discussions, serving once more as a beacon for Black American patriotism. These writers and activists were rebuffed along the way by whites who denounced and mocked Attucks during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as “a rowdyish person,” “a drunken and disreputable half-caste,” and as a “transient visitor” who was “itching for a fight” and was “not a very useful member of society.” Despite these insults, Attucks’s legacy continued to grow. As the civil rights movement gained momentum in the middle of the twentieth century, Attucks appeared more often in popular publications like books and magazines, where his story was shared with wider audiences. Today, Attucks’s memorialization on everything from a bridge in Framingham to schools across the country testify that he has not been forgotten, and serve as public reminders that people of color have always been important contributors to America’s history.

Close Reading Questions

- Source 1: Newspaper Account of the Boston Massacre, 12 March 1770

-

Close Reading Questions:

- What language / phrasing does this source use when referring to the victims of the Boston Massacre as a collective group? How does this language reflect the way the authors see this event?

- What language / phrasing does this source use when addressing Crispus Attucks? How does this language reflect the way the authors see him as a person?

- Source 2: James Bailey discusses Crispus Attucks in his trial testimony (benefitting the Defense)

-

Close Reading Questions:

- If you were the defense lawyer representing the British soldiers (as John Adams was), what words / phrases in Bailey’s testimony would have been most helpful in proving that the soldiers acted in self-defense? Why?

- Based on Bailey’s testimony of the events of 5 March 1770, how would you summarize Crispus Attucks’ role that night?

View Source (full testimony: image #24-28).

- Source 3: James Brewer discusses Crispus Attucks in his trial testimony (benefitting the Prosecution)

-

Close Reading Questions:

- If you were the prosecution lawyer looking for evidence that the British soldiers were the aggressors the night of the Boston Massacre, what words / phrases in Brewer’s testimony would have been most helpful in proving your argument? Why?

- Based on Brewer’s testimony of the events of 5 March 1770, how would you summarize Crispus Attucks’ role that night?

View Source (full testimony: image #20 - #24).

- Source 4: John Adams’ Blames Crispus Attucks for the Boston Massacre in his Closing Argument for the Defense

-

Close Reading Questions:

- According to Adams’ closing argument, why should the jury find the British soldiers not guilty of murder?

- How does Adams characterize Attucks? Which witness testimony does Adams rely on to make his closing argument?

- Why might Adams have chosen to frame Attucks’ role in the event in this way?

- On the third anniversary of the Boston Massacre, Attucks wrote in his diary that his defense of the British soldiers was “one of the best Pieces of Service I ever rendered my Country. Judgment of Death against those Soldiers would have been as foul a Stain upon this Country as the Executions of the Quakers or Witches, anciently.” (View diary entry: 1773. March 5th. Fryday.) Based on the sources you have read, do you agree or disagree with Adams’ assessment of his defense?

View Source (Adams’ full closing argument spans image #148 - #178).

- Source 5: John Hancock Remembers the Boston Massacre, 5 March 1774

-

Close Reading Questions:

- The highlighted quote from John Hancock’s oration is directed both toward those who planned the placement of British troops in Boston and the soldiers who carried out the Boston Massacre itself. What do you think Hancock is asking of these individuals with his rhetorical question?

- Why might Hancock have utilized the specific names of those who died in the Boston Massacre at this point in his oration? Do you think it makes the point more or less effective in critiquing the parties it is addressed to?

- Source 6: Historian William C. Nell describes Crispus Attucks’ role in the Boston Massacre, 1855

-

Close Reading Questions:

- How would you summarize how William Nell felt about the denial of his petition for a statue to honor Crispus Attucks?

- Considering the excerpts on Crispus Attucks and the greater context of Nell’s 1855 book The colored patriots of the American Revolution: with sketches of several distinguished colored persons: to which is added a brief survey of the condition and prospects of colored Americans, what do you think his main purpose was in publishing this text at this particular time in American history?

View The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution (1855), digitized by Documenting the American South, UNC.

- Source 7: 1856 Artist Depiction of the Boston Massacre

-

Close Reading Questions:

- Upon examining this depiction of the Boston Massacre, what words do you think best capture the mood or energy of the scene?

- What role does this artist believe Crispus Attucks played in the Boston Massacre? (Consider his placement of Crispus Attucks in the scene.) Does Nell’s quote support or oppose the depiction of Attucks in the image?

- Compare this image to Paul Revere’s original 1770 engraving. How are the two images different? How is Crispus Attucks depicted? What does each image say about the time in which it was created?

- Note for teachers: Revere depicts all of the victims as white men, whitewashing Attucks and his participation, and death, that night.

- Source 8: “Martyrdom of the colored American Crispus Attucks!” Broadside

-

Close Reading Questions:

- How does this poster characterize Crispus Attucks and his role in the Boston Massacre?

- How does this broadside connect the legacy of Crispus Attucks to events occurring in the 1860s in America?

- Do you think Crispus Attucks was a martyr? Why/why not?

For teachers who want to do a close reading of the broadside, use these slides as a key to identify all of the references in this broadside. (Google Slides)

Suggested Activities – Elementary

- Comparing and Analyzing Images

-

Materials:

Paul Revere’s 1770 engraving of the Boston Massacre

Bufford’s 1856 engraving of the Boston Massacre

Boston Massacre Image Analysis Worksheet

Activity Overview: Students look closely at two depictions of the Boston Massacre made 85 years apart, and read a quote that supports each image. Then, they work to identify similarities in and differences between the two images. This activity prepares students to participate in a flash debate.

- Flash Debate: Using Evidence to Support a Claim

-

Materials:

Flash Debate worksheet and teacher directions

Paul Revere’s 1770 engraving of the Boston Massacre

Bufford’s 1856 engraving of the Boston Massacre

Prior Knowledge:

For a successful debate, students should already have completed one or more of the previous activities so that they have a better understanding of different descriptions of what happened on the night of March 5, 1770:

Boston Massacre Witness Testimony Gallery Walk

Boston Massacre Image Analysis and Comparison

Boston Massacre Close Reading: Primary Source

Activity Overview: A Flash Debate provides an opportunity for students to make a well-constructed argument, while developing speaking and listening skills. Using the prompt, “Which of the two images provides the most accurate account of the events of March 5, 1770?” students choose a side, caucus with peers on their side to discuss relevant evidence, and then face-off against peers on the other side of the debate.

Suggested Activities – Grades 8-12

- Hook

-

Materials:

Crispus Attucks: Hook Activities Document

Activity Overview: Choose one of four different warm-up activities to begin a whole class discussion about who we remember from the past, and why. This will prepare students to dive into this source set on Crispus Attucks, and the different ways in which he was publicly remembered between 1770 and 1863.

- Comparing Depictions of the Boston Massacre

-

Prior knowledge:

Materials:

The Bloody Massacre, 1770, Paul Revere

Boston Massacre, March 5th 1770, 1856, William Champey

“Comparing Depictions of the Boston Massacre” Handout

Activity Overview: Students use an Observe-Interpret-Question graphic organizer and Purpose/Point of View Questions to help them answer an analysis writing prompt. The analysis can be completed independently, or students can work in small groups or pairs to complete the analysis before writing independently.

- John Adams & Shaping the Immediate Narrative Around Crispus Attucks

-

Prior Knowledge:

Materials:

Sources 2 and 3: Trial Testimony excerpts: Brewer and Bailey

“John Adams & Shaping the Narrative Around Crispus Attucks” Handout

Activity Overview: Students use what they have learned from trial testimony and Adams’ closing argument to assess Adams’ own analysis of his role in the trial in a diary entry from March 5, 1773. This can be done independently, in pairs, or in small groups.

- Visual Analysis of the “Martyrdom of Crispus Attucks” broadside

-

Materials:

“Martyrdom of Crispus Attucks,” 1863 broadside

Visual Analysis of the “Martyrdom of Crispus Attucks” Google Slides

Teacher’s Guide: Notes to the Google Slides

Activity Overview: As a class, students do a close reading of the broadside, with the teacher providing context and background information as needed (provided in teacher guide and slide deck “notes”). Students then respond to questions on the final three slides in discussion with a partner, or independent writing. This visual analysis helps students to better understand the role of abolitionists in reinterpreting Crispus’ Attucks legacy, and the role of commemorative events in changing public perceptions of the past.

- Design a Memorial

-

Prior knowledge:

Materials:

Activity Overview:

Using their knowledge of the sources in this source set, students work independently or in small groups to:- Write a request to the Massachusetts state government for a monument to Crispus Attucks

- Provide a sketch of a design for the monument

- Write a caption for the monument’s plaque

Critical thinking questions guide students to consider their purpose, audience, and more in their monument design.

Applicable Standards

- MA History/Social Science and ELA Frameworks

-

H/SS Skill Standards

Demonstrate civic knowledge, skills, and dispositions.

Organize information and data from multiple primary and secondary sources.

Argue or explain conclusions, using valid reasoning and evidence.H/SS Content Standards

Grade 3, Topic 6. Massachusetts in the 18th century through the American Revolution

Analyze the connection between events, locations, and individuals in Massachusetts in the early 1770s and the beginning of the American Revolution, using sources such as historical maps, paintings, and texts of the period; the Boston Massacre (1770), including the role of the British Army soldiers, Crispus Attucks, Paul Revere, and John AdamsGrade 5, Topic 2. Reasons for revolution, the Revolutionary War, and the formation of government

On a historic map of the Boston area in the 1770s, locate important sites in the preRevolutionary and Revolutionary period and analyze the role and the significance of Massachusetts people such Samuel Adams, Crispus Attucks, John Hancock, James Otis, Paul Revere, John and Abigail Adams, Mercy Otis Warren, Phillis Wheatley, Peter Salem.USH.1. Topic 1. Origins of the Revolution and the Constitution

Describe Patriots’ responses to increased British taxation (e.g., the slogan, “no taxation without representation,” the actions of the Stamp Act Congress, the Sons of Liberty, the Boston Tea Party, the Suffolk Resolves) and the role of Massachusetts people (e.g., Samuel Adams, Crispus Attucks, John Hancock, James Otis, Paul Revere, John and Abigail Adams, Mercy Otis Warren, Judith Sargent Murray, Phillis Wheatley, Peter Salem, Prince EstabrookELA Core Anchor Standards

Reading

- Analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take

Writing

- Conduct short as well as more sustained research projects based on focused questions, demonstrating understanding of the subject under investigation

Speaking and Listening

- Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively.

- Integrate and evaluate information presented in diverse media and formats, including visually, quantitatively, and orally.

- C3 Frameworks

-

D1.1.9-12. Explain how a question reflects an enduring issue in the field.

D1.5.9-12. Determine the kinds of sources that will be helpful in answering compelling and supporting questions, taking into consideration multiple points of view represented in the sources, the types of sources available, and the potential uses of the sources.

D2.His.3.9-12. Use questions generated about individuals and groups to assess how the significance of their actions changes over time and is shaped by the historical context.

D2.His.5.9-12. Analyze how historical contexts shaped and continue to shape people’s perspectives.

D2.His.12.9-12. Use questions generated about multiple historical sources to pursue further inquiry and investigate additional sources.

Additional Resources

Additional Resources

- Differing depictions of Crispus Attucks in Paul Revere’s engraving

-

Paul Revere created The Bloody Massacre (1770) engraving after an image first made by Henry Pelham. Most existing copies of Revere’s engraving, including the one held by the Massachusetts Historical Society, depict all of the victims – and everyone in the crowd – as white. However, there are copies that depict Crispus Attucks as a person of color. Four such examples can be seen below. Although all four versions differ from one another in certain respects, they all depict the same victim as Attucks, perhaps identifying him by the placement of his wounds.

Paul Revere Collection at the American Antiquarian Society

This copy of Paul Revere’s 1770 engraving The Bloody Massacre was hand-colored by Christian Remick (b. 1726). Crispus Attucks is shown on the bottom-left, with his face upside-down. Although his skin is white, his hair in this print appears much darker than that of any other figures.

Paul Revere’s engraving of the Boston Massacre, 1770 | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History

This version of Revere’s The Bloody Massacre features a slightly shaded depiction of Attucks, which may denote his race, and with hair that is blotched as black as the other Bostonians' hats. This image is courtesy of the Gilder Lehrman Institute, and the webpage also includes slides analyzing aspects of the entire engraving.

The Bloody Massacre - Free Library

This more heavily shaded version of Revere’s The Bloody Massacre print clearly depicts Attucks as a man of color. The image is held by the Free Library of Philadelphia.

Most copies of Paul Revere’s 1770 engraving of the Boston Massacre depict all of the victims – and the people in the crowd – as white. This hand-colored copy, held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, clearly depicts Crispus Attucks as a person of color.

- Black Witnesses to the Boston Massacre and Black Participation in the Revolutionary War

-

Black Witnesses to the Boston Massacre

Crispus Attucks was not the only Black or mixed-race person to be part of the crowd in Boston on March 5, 1770. Newton Prince and Andrew (last name once known) were two Black men who gave witness testimony at the trial of the British soldiers.

Newton Prince was a married, free Black lemon merchant and pastry chef. He was also a member of Old South Church. When war broke out, Prince and his wife traveled to London where he filed for and received a Loyalist pension from the British government.

Andrew was enslaved by Oliver Wendell, who was a member of the Sons of Liberty. Andrew’s testimony implicated Crispus Attucks as a leader of the protest.

The above Google doc contains notes on their testimonies as recorded “Anonymous Summary for the Defense” in the Adams Papers Digital Edition. Read Prince’s testimony in the published pamphlet, “The Trial of William Wemms, James Hartegan, William McCauley, …" 1770, beginning here. Read Andrew’s testimony as printed in the trial pamphlet, beginning here. The pamphlet index identifies both men as Black, and does not identify any other witnesses of color.

This broadside lists the names and towns of men who were killed and wounded at the Battle of Lexington & Concord. Among the wounded was Prince Easterbrooks (alternatively spelled “Estabrooks”), a Black man from Lexington.

The Battle at Bunker's Hill Near Boston. June 17, 1775. (use-iphone.com)

This engraving was copied from John Trumbull’s 1786 painting of the Battle of Bunker Hill. In the bottom-right part of the image, an armed Black man can be seen standing behind a white man. Long thought to depict an enslaved man named Peter Salem, scholars now believe the man to be Asaba, who was enslaved by Lieutenant Thomas Grosvenor.

In this Massachusetts Historical Society podcast episode, historians Ben Remillard (University of New Hampshire) and J.L. Bell discuss what we do and do not know about the Bucks of America, believed to be an all-Black regiment of the Continental Army.

James Forten Discovery Cart - Museum of the American Revolution (amrevmuseum.org)

Born to free Black parents in Philadelphia in 1766, James Forten served aboard numerous privateer ships during the Revolutionary War. Learn more about Forten, as a young person and adult, at the Museum of the American Revolution website.

- Crispus Attucks and the 1850s Abolitionist Movement

-

First Anniversary of the Kidnapping of Thomas Sims, by the City of Boston (use-iphone.com)

The passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law endangered Black people who had fled slavery and sought freedom in northern, non-slaveholding states. In 1851, Thomas Sims traveled to Boston after fleeing slavery in Georgia, but was caught and forcibly re-enslaved. This 1852 broadside marks the 1-year anniversary of Sims’ capture and connects commemorations of the Boston Massacre and Independence Day to the goals of abolitionists saying, “Our fathers commemorated the Massacre of the fifth of March, 1770, til that dark hour was lost in the blaze of the Fourth day of July, 1776, and the events which followed it. It is for us, likewise, to keep before the people of the Commonwealth [Massachusetts] the late infamous deed of the City Government until it be atoned for and forgotten in the joy of a General Emancipation.”

The Liberator (Boston, Mass. : 1831-1865) - Digital Commonwealth

Between 1850-1865, numerous articles in the Liberator, William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper, made reference to Crispus Attucks. For example, the 30 June 1854 issue reprinted an article from the Worcester Spy that decried Anthony Burns’ capture in Boston and forcible return to slavery in Virginia under the Fugitive Slave Act. That article said, “Thousands of people came out to see the preacher [Burns] led off to slavery over the spot where Hancock stood and Attucks fell, and the soldiers, with their bayonets at people’s throats, and the muzzles of their muskets at their heads, compelled them to be still. . .

Another article, from 21 November 1856, makes reference to the Attucks Blues, a military company of Black men in Ohio named in honor of Crispus Attucks who the article called “the first martyr in the Revolution.”

- Crispus Attucks and the 1619 Project

-

1619 Project_Crispus Attucks Poem

“First to Rise” is a poem about Crispus Attucks by the poet Yusef Komunyakaa. “First to Rise” appears in the New York Times’ 1619 Project. In his poem, Komunyakaa quotes a portion of John Adams’ closing argument in the trial of the British soldiers, in which Adams blames Black and mixed race men, Irish immigrants, and “jacktars” (seafarers) for the Boston Massacre.Activities to Extend Student Engagement | Pulitzer Center: 1619 Project (1619education.org)

In addition to essays, The 1619 Project, edited by Nikole Hannah-Jones, features poems and short stories that are a “creative interpretation of a historical figure or event that either doesn’t get the attention it deserves, or is often misinterpreted.”

The Pulitzer Center Education has resources to deepen student engagement with the 1619 Project. In Lesson 7 “Reframing History Through Creative Writing,” students read Nikole Hannah-Jones’ essay “The Idea of America,” in addition to a selection of the creative works in The 1619 Project. For this source set, students could read Komunuakaa’s poem about Crispus Attucks, “First to Rise.” Then, students discuss the poem and write their own poem about Crispus Attucks.

Find a reading guide for the creative works in The 1619 Project here. - Secondary Sources on Crispus Attucks

-

The colored patriots of the American Revolution : with sketches of several distinguished colored persons : to which is added a brief survey of the condition and prospects of colored Americans, by William C. Nell ; with an introduction by Harriet Beecher Stowe, R.F. Wallcut: Boston, 1855.

(Documenting the American South)

Read an electronic edition of Nell’s 1855 book that is quoted in the source set.

Episode 230: Mitch Kachun, First Martyr of Liberty - Ben Franklin's World (benfranklinsworld.com)

In this podcast episode, Professor Mitch Kachun discusses Crispus Attucks and public memory.

The American Scholar: Black Lives and the Boston Massacre (Farah Peterson, The American Scholar)

In this article, the legal historian Farah Peterson (University of Chicago Law School) reconsiders the legacy of Crispus Attucks and his portrayal at the trial of the British soldiers.

The Hidden Life of Crispus Attucks - Journal of the American Revolution (allthingsliberty.com)

In this article, the writer Jerome Palliser examines primary sources to show what we do and do not know about Crispus Attucks, and his role in the Boston Massacre.

Comparing coffins, remembering the Boston Massacre | National Museum of American History (si.edu)

This article from the Smithsonian National Museum of American History examines the images of the coffins of the five victims that appeared in contemporary broadsides and newspaper coverage of the Boston Massacre.

- Picture Books about Crispus Attucks

-

- Crispus Attucks and The Boston Massacre by Monica Reed, 2021

- Kid friendly, has primary sources, images related to Attucks’ life, student activities, etc.

- The Stories of Crispus Attucks, John Adams and Paul Revere: Heroes of the American Revolution, 2020

- Includes historical images, some graphic artwork, one paragraph per page making the read very friendly for students.

- Crispus Attucks and African American Patriots of the American Revolution by Brian Siddons, 2016

- Crispus Attucks: Hero of the Boston Massacre by Anne Beier, 2003

- Crispus Attucks: Black Leader of Colonial Patriots by Gray Morrow, 1986

- Crispus Attucks and The Boston Massacre by Monica Reed, 2021