By Neal Millikan, Series Editor for Digital Editions, The Adams Papers

Transcriptions of more than 1,400 pages of John Quincy Adams’s diary have just been added to the John Quincy Adams Digital Diary, a born-digital edition of the Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society. The new material spans the period January 1839 through December 1842 and chronicle Adams’s involvement with the Amistad court case as he also continued serving in the United States House of Representatives.

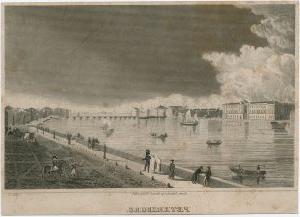

In July 1839, fifty-three Africans revolted aboard the Spanish slave ship Amistad as they were being transported by their enslavers from Havana to another Cuban port. During the revolt, the Africans killed the ship’s captain and another crew member, demanding to be returned to Mendiland (now Sierra Leone). However, the remaining Amistad crew were able to divert the vessel from its course. On 24 August a U.S. revenue cutter seized the Amistad off Long Island and brought it into the port of New London, Connecticut. The Africans were imprisoned at New Haven, Connecticut, while their case moved through the U.S. District and Circuit Courts.

While he offered opinions and advice on the Amistad case as early as September 1839, John Quincy Adams did not take a formal role until a year later. Abolitionists visited the former president at his home in Quincy on 27 October 1840 and convinced him to join the Amistad defense team when the case went before the U.S. Supreme Court. In his diary, Adams noted his reluctance to provide further legal counsel. “I endeavoured to excuse myself upon the plea of my age and inefficiency—of the oppressive burden of my duties as a member of the House of Representatives, and my inexperience after a lapse of more than thirty years . . . before judicial tribunals.” However, the abolitionists “urged me so much and represented the case of those unfortunate men as so critical, it being a case of life and death, that I yielded.”

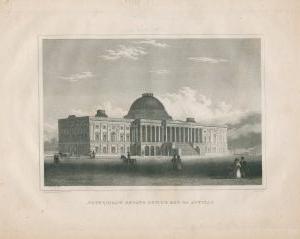

The trial opened in February 1841. John Quincy Adams began his oral arguments for the defense on the 24th, speaking for “four hours and a half, with sufficient method and order to witness little flagging of attention, by the judges or the auditory.” Pleased with his performance, he modestly assessed: “I did not I could not answer public expectation—but I have not yet utterly failed.” Adams returned to the court on 1 March to conclude his argument on behalf of the Amistad Africans and spoke for another four hours. The court’s opinion, delivered on 9 March, ruled that the Africans were free and could return home.

As he revised for publication his oral arguments in the Amistad case, John Quincy Adams mused in his diary on the current state of the emancipation cause in the United States. “The world, the flesh, and all the devils in hell are arrayed against any man, who now, in this North-American Union, shall dare to join the standard of Almighty God, to put down” the issue of slavery. He lamented that his own physical infirmities prevented him from doing more to further the cause. “What can I, upon the verge of my seventy-fourth birth-day, with a shaking hand, a darkening eye, a drowsy brain, and with all my faculties, dropping from me, one by one, as the teeth are dropping from my head . . . what can I do for the cause of God and Man? for the progress of human emancipation? . . . Yet my conscience presses me on.” The following year, Adams recorded that his continued opposition to slavery produced considerably different reactions in the North and South. While northerners routinely wrote to him asking for an autograph, the letters he received from southerners often contained “insult, profane obscenity and filth.”

For more on John Quincy Adams’s life, navigate to the entries to begin reading his diary. The addition of material for the 1839–1842 period joins existing transcriptions of Adams’s diary for his legal, political, and diplomatic careers (1789–1817), his time as secretary of state (1817–1825), his presidency (1825–1829), and his early years in the House of Representatives (1830–1838) and brings the total number of transcriptions freely available on the MHS website to more than 9,800 pages.

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our sponsors. Major funding for the John Quincy Adams Digital Diary was provided by the Amelia Peabody Charitable Fund, with additional contributions by Harvard University Press and a number of private donors. The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation in partnership with the National Historical Publications and Records Commission also support the project through funding for the Society’s Primary Source Cooperative.